Anatomy of a Status Page

When I first started in the tech industry, a new idea was on the scene for your service’s status page: just embed the company’s Twitter (now X) account on a page. Since we were all using Twitter constantly, it was the best place to check for updates about our service. These days, our expectations for a critical service’s status page are a bit higher than the occasional social media post. This article helps define what users expect in a status page, and the technical requirements.

What users expect from a status page

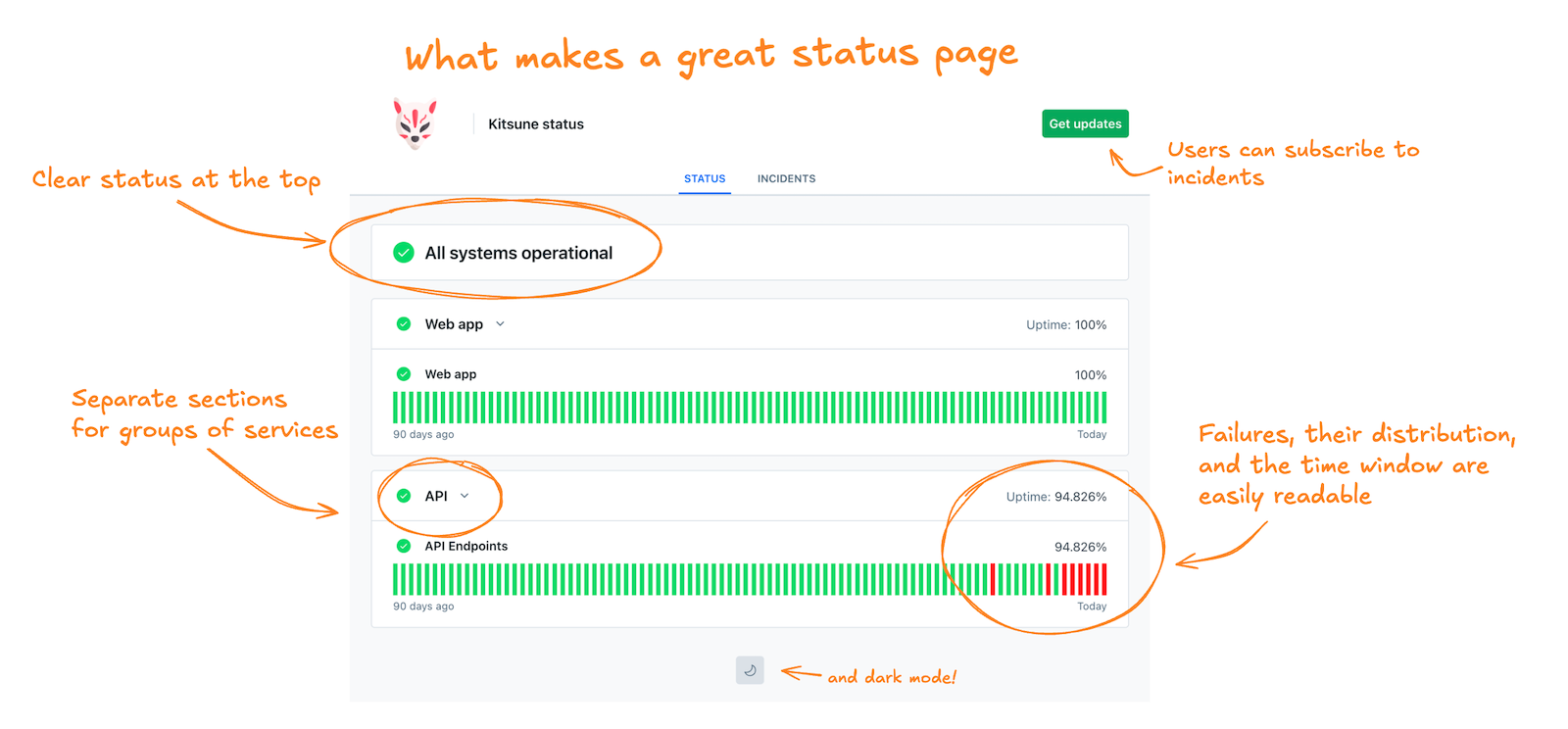

A status page helps users know if your applications or services are working. Here’s what users expect from a good status page:

1. Clear Status Updates

- Show if services are up, down, or having issues.

- Use simple labels (like “Operational,” “Degraded,” or “Outage”).

2. Externally Hosted

- The page should be on a separate system (not your main website). This way, users can check it even if your site is down.

3. Subscribe Function

- Let users subscribe to updates via email, SMS, or RSS.

- Notify them when status changes.

4. Easy for Everyone to Use

- Regular users should understand it easily.

- Application owners should be able to manually mark a service as down if needed.

5. Multiple Sections

- Support different audiences (e.g., one page for customers, another for internal teams).

- Let users subscribe only to the pages they care about.

A good status page keeps users informed, reduces frustration, and builds trust. Make sure yours is simple, reliable, and easy to follow.

Technical requirements for a good status page

The basic technical requirements (fast loading pages, manual edits permitted, etc) aren’t worth mentioning, but the following features will require some ‘lift’ on any DIY solution, and aren’t offered by every SaaS status page tool.

1. Automated monitoring - no matter how slick our status page, if we’re relying on users to report most outages, our status page is worse than useless. Implicit in the requirements above is that most outages and incidents will be detected automatically and added to a status page. The best way to determine your service status automatically is through synthetic monitoring, ideally using Playwright to simulate user paths in detail.

2. Independent hosting - ideally both your monitoring and the status page will be hosted away from your service’s cloud. Even AWS are vulnerable to failures where the monitor (and its notifications) failed in the same outage that took down the service, adding significantly to time to repair.

3. Clear infographics - a status page should be able to take complex historical data and turn it into a clear history for the viewer. Some kind of graphing library should represent high level status data visually.

4. Incidents should be organized into services - for Checkly’s Status Pages, all alerts are classified ahead of time into services. We don’t want to present our product as a monolith, nor should we print inscrutable internal labels. With this organization, we can present sections on a single status page, or multiple separate status pages with groupings of services.

5. Subscription service - Users should subscribe to only the pages they care about.

Conclusions: for status pages brevity, is wit

In short, a good status page keeps users informed and builds trust. It must be clear, reliable, and easy to use. Users want quick updates, simple labels, and the ability to subscribe. On the tech side, it needs automated monitoring, independent hosting, and clear visuals. By meeting these needs, your status page will help users stay updated and reduce frustration.

Further reading: A guide to Checkly’s Status Pages